Synopsis from Linucon program book: "Science Fiction authors we like, even though we think we shouldn't."

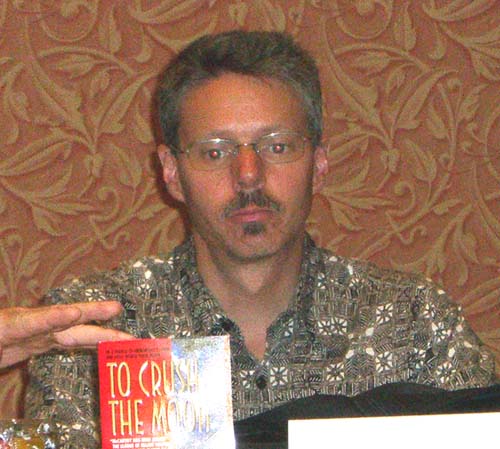

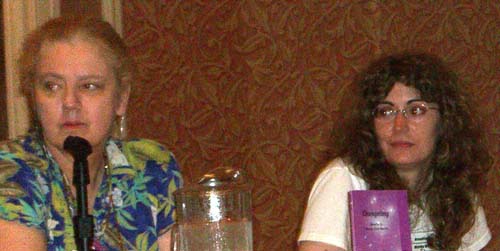

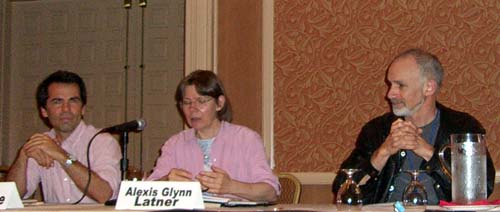

The panelists were Cathy and Eric Raymond. The audience enthusiastically joined into sharing their own guilty pleasures. Although I have read only one author out of the ones mentioned on the panel, I found this panel to be fun. Just to hear the plot summaries, funny details and even the titles of other people's favorite trashy books was hilarious.

Examples of hilarious titles and plot snippets

Titles: "Snow White and the Seven Samurai", or "Who's Afraid of Beowulf" (both by Tom Holt).

Plot snippets:

Cathy Raymond, recounting the plot of I don't remember what book. There's this wizard that goes on this quest and he has only one advantage...

Eric Raymond. An elderly mentor whose entire vocabulary consists of the word "indeed".

Cathy. He has a curse or attribute that he can never truly be alone for more than a second at a time. Which means that death can't nab him, because death has to go after him when he's alone, and he never is.

And:

Rob Landley. I dug up some old books "The Girl With The Silver Eyes" and such, where very little actually happens, but it's a really good book. It's a book about a telekinetic finding three other telekinetics due to something their mothers have taken as a headache medicine. They find out they WEREN'T actually being tracked by the government. It's one of those books where if they had been adults, it would have taken them 45 minutes and a car to find out.

I checked the names and titles of most authors and books mentioned in this post, but if some are misspelled, it is solely my fault.

So, here are our panelists' and audience's guilty pleasures.

Panelists' and audience's guilty pleasures

Eric Raymond. Honor Harrington series.

Cathy Raymond. Conan the Barbarian.

Eric Raymond. For me, military SF in general is a guilty pleasure cause most of it is crap. There are some fine ones, like Lois Bujold and Robert Heinlein. But those are exceptions. The rest of military SF is crap. But I read them anyway. I cut my teeth on Doc Smith [with his gigantic space battlefields blowing up] and I enjoy them.

Eric Raymond further mentions having enjoyed the Star Kings novel by Edmond Hamilton, and its sequel. That's actually the only two novels of the ones mentioned in this discussion, that I (Elze) have read. And they were delicious!

.

Cathy Raymond. Laurel K. Hamilton. She writes some wonderful fantasy wedging fantasy creatures rather convincingly into real world settings. She writes really well but that's not why I read her. I read her because of sex.

A woman in the audience. Soft porn.

Cathy. I wouldn't say soft porn. Some of it is really graphic.

Another woman in the audience brings up Anne Rice.

Cathy. I should have thought of her for the other panel (Authors We Gave Up On), because I've given up on her. She was even more in the soft porn direction, although not as good at is as the other authors.

Rob Landley. I like reading children's books, science fiction books that are aimed at young adult market. They have them in a section with big bright colors with baloons. I just grab books and take them home. Well, I pay for them first.

(Everyone laughs, and someone shouts: Now that would be a REAL guilty pleasure!)

Jay Maynard. I've got one. A Star Trek novel "How much for just the planet"?

Eric Raymond. It had a virulent anticapitalist political ranting in it, and [despite that] Jay and I both liked it. That's how good it was!

Jay Maynard. It's been described as Hitchiker's Guide to the Federation. If you put the book down ater the first 20 pages, you have no sense of humor at all.

Rob Landley says when he was 10, his parents visited Andre Norton in Florida. His father was this huge fan of hers. So he met this fat lady with veins in her legs and couldn't stand up very well, and had cats. She had books all over the place. She gave Rob a book based on D&D. She described it as "over most major plot turns you can hear the dice roll".

Then again, one person's guilty pleasure can be another person's brilliant satire. This leads the panelists to a debate on...

How does one define a guilty pleasure?

A guy in the audience lists a book "First Contract" (aliens make a contact with us and it turns out they're capitalists). Eric thinks it's a satire, not a guity pleasure. So are, in his opinion, Stainless Steel Rat stories, which another audience member counts as his guilty pleasure. So what differentiates a GP from a book you're willing to admit you like? asks Cathy.

Eric Raymond. I can put my finger on one difference. Most guilty pleasure have in common that the author is barefacedly trying to manipulate the reader in ways that are rewarding but have nothing to do with actual story or idea, or anything that rises to the forebrain level. First Contract makes an interesting case. There's a level of wit and cleverness in that book. There's a level of author sharing with you a sardonic commentary on that book that actual guilty pleasures don't have.

That's what GP have in common with pornography.

Eric Raymond. Terry Pratchet for me, when he was just doing lightweight satirical comedy, there was a touch of guilty pleasure about him too, but then he got all wise and I don't feel guilty reading him anymore.

A guy in the audience takes a different tack on the topic. My guilty pleasure is anything by De Sade. I did a monologue from him in my acting class. More than anything else he convinced me to leave the church. His ideas on welfare were also very extreme. That's a guy who makes Ayn Rand look tame, and that's hard to do.

Cathy acknowledges that that's a different topic: ideas so radical that even in this society they are not acknowledged.

How do the panelists have time to read so much?

Noticing that Eric Raymond has read pretty much every book that anyone in the audience has mentioned, someone asks: "How do you have time to read all this stuff?"

Eric Raymond says he reads faster than anyone he knows. He and Jay Maynard compare their reading speeds.

Cathy Raymond says she read the latest Harry Potter book on a Saturday afternoon when she had nothing else to do and it took her about 5 hours.

Eric Raymond. I thought I read faster than anyone else I know. But occasionally I think she reads faster than me.

Cathy. No, I ignore more shit.

Cathy offers a partial explanation to how Eric managed to read so many books in his lifetime. He has been a hacker for more than 20 years, and back then when you compiled, you had oodles of downtime, so he would read.

He has read so much that he issues a challenge to the audience: "if you can remember anything enough about a guilty pleasure that you don't know the title of, I can probably identify it." And then it turns out that he can't actually name any of the three books that the audience members ask him to identify.